🤦🏻 关于我:ex京东用户中心负责人,也在ebay、阿里混迹过。 🍵《青陈》是关于「产品文化广义阅读」的专栏,涉及「商业、思维、设计、文化、审美」等话题,抵制一切成功学和「干货」 🐈 每周1-3篇原创文章或分享阅读。会员权益见「详细介绍」。

关于近期断更的说明和后续计划

首先,这个项目会一直做下去。预计本周开始复更。

关于最近断更的问题,无论怎样解释都是给自己找借口,涉及我自己搬到海外居住和工作内容的一些变化,不赘述,断更总是不对的,先道歉。

......Letter #033 未经审视

本期内容共6964字,阅读时长约40分钟。(只统计原创和批注文字,不包含分享的原文献)

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入......

Letter #032 优势的囚徒

本期内容共6766字,阅读时长约40分钟。(只统计原创和批注文字,不包含分享的原文献)

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入......

Letter #031 产品的第一性原理

本期内容共5121字,阅读时长约30分钟。

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入。

本期内......小假条

常年痼疾又犯,鼻炎甚是严重,头痛不止。本周四应更新的Letter# 030未能及时发送,会在下周(4.22日前)随Letter #031一并补齐。

望海涵

......

Letter #030 在平庸年代保持莽撞

本期内容共7021字,阅读时长约40分钟。

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入。

本期内容图鉴<......

不开始音乐会,就无法学习小提琴

“塞缪尔·巴特勒说,生活就像是一边在学拉小提琴,一边开音乐会——朋友们,这是真正的智慧。我不厌其烦地引用这句话。”

— Saul Bellow

Letter #029 把错过当做生活的本质

本期内容共6056字,阅读时长约30-40分钟。

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入。

本期内容......

Letter #028 不必为AI焦虑

本期内容共7924字,阅读时长约40-50分钟。

所有分享文章的原文,可在Notion会员知识库中直接阅读,已订阅用户请联系我进入。

本期内容......

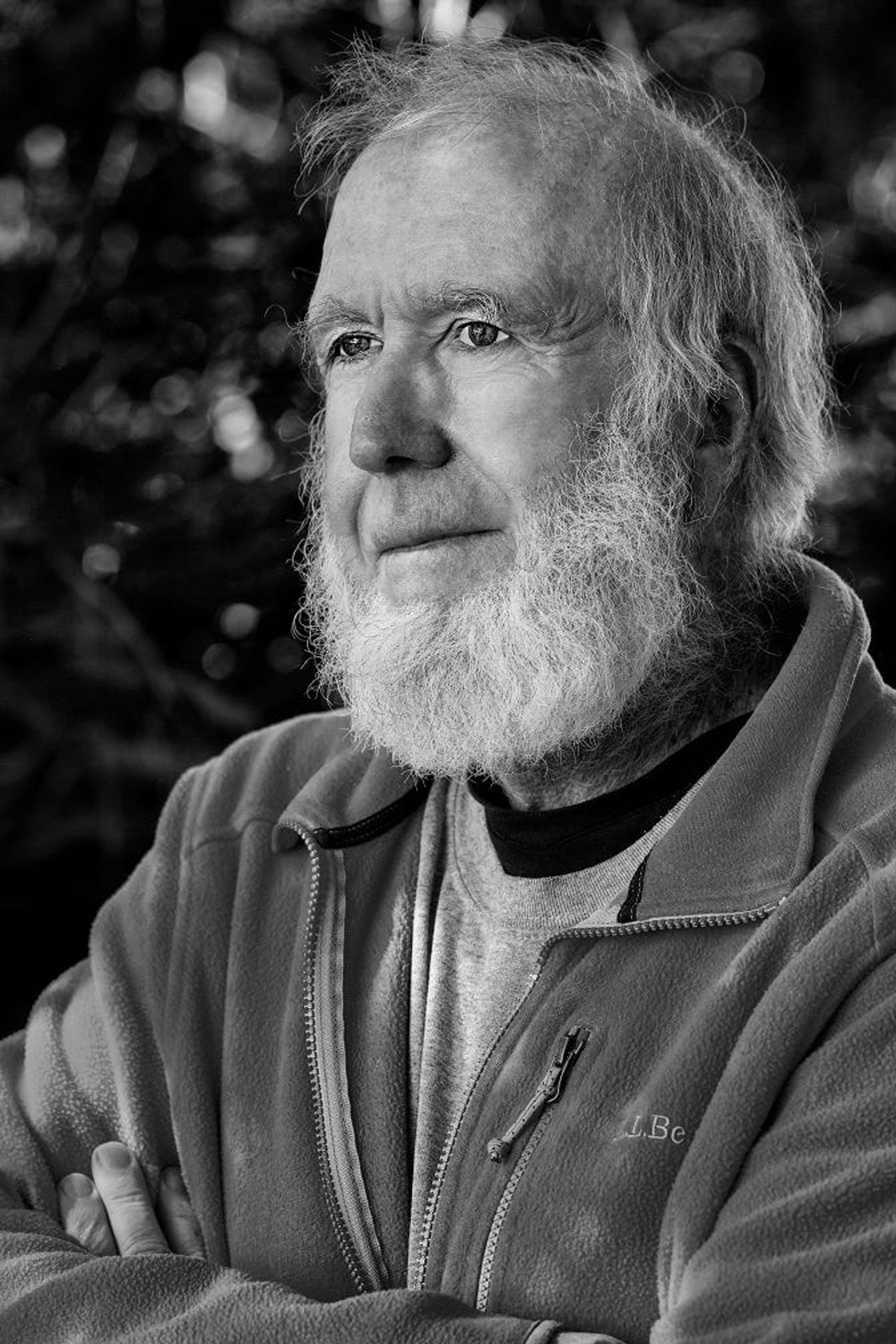

K.K最新专访 简译 Interview: Kevin Kelly, editor, author, and futurist

本期内容是 青陈 #027 技术向善吗 中KK专访部分的采访资料补充,方便没进入Notion的会员和读者阅读。Noah Smith和K.K的谈话信息量很大,涉及技术与人类的关系、AI、Web3等话题,而K.K无疑是相当具有发言权的人。

以下为原文全文,翻译使用ChatGPT完成,配合部分的手工校验:

Interview: Kevin Kelly, editor, author, and futurist

Kevin Kelly is one of the thinkers who helped define the ethos of the tech industry from its early days. As an editor of the Whole Earth Catalog in the 1980s and the founding editor of Wired magazine, he helped to integrate environmentalism and optimistic techno-futurism into a worldview that deeply influenced generations of founders, engineers, and creators. His work is so wide-ranging that it’s hard to sum it up in simple terms (I asked ChatGPT for help, but it could only give me vague generalities). His books and articles are a mix of technological prediction, interpretation 83 of the current zeitgeist, and philosophical exploration.

Interestingly, his most recent book, Excellent Advice for Living: Wisdom I Wish I'd Known Earlier, is a book of life advice! His intellectual breadth and ability to synthesize various seemingly unrelated trends and ideas are something to 5 I can only aspire.

Essentially, if you look at the fast-changing world of technology and you ask “Where is this all headed?”, and “Where should this all be headed?”, then Kevin Kelly is a natural person to ask. And in the interview that follows, that is basically what I asked him. I especially focused on his idea of the “technium”, which is all of human technology acting together as a single natural system or organism. We talk about whether this technium exists in competition with Earth’s natural environment, or whether the two can exist in harmony. We also discuss AI, social media crypto, and we talk about whether and how technological development can be actively steered. He also dispenses a bit of helpful life advice.

Kevin Kelly是帮助定义了科技产业的伦理道德的思想家之一,从早期起就担任《全球地球目录》的编辑和《连线》杂志的创始编辑,他帮助将环保主义和乐观的技术未来主义融入了一个世界观中,深刻影响了创始人、工程师和创作者的几代人。他的工作范围非常广泛,很难用简单的术语来总结(我向ChatGPT寻求帮助,但它只能给我一些模糊的概括)。他的书籍和文章涵盖了技术预测、当前时代精神的解释和哲学探索等多种方面。有趣的是,他最近的书,《卓越人生建议:我希望早些知道的智慧》是一本人生建议的书!他的广泛智识和综合各种看似无关的趋势和思想的能力是我所仰慕的。

实际上,如果你看看快速变化的技术世界,你会问“这一切将走向何方?”和“这一切应该走向何方?”那么询问Kevin Kelly是再合适不过了。在接下来的采访中,我特别关注了他的“技术体”,即将所有人类技术作为一个单一的自然系统或有机体来行动。我们讨论了这种技术体是否与地球的自然环境竞争,或者这两者是否可以和谐共存。我们还讨论了人工智能、社交媒体、加密货币,以及我们谈到了技术发展是否可以被积极引导。他还给出了一些有用的人生建议。

N.S.: So first let's talk about your new book, Excellent Advice for Living. What made you decide to write a book of life advice?

N.S.:首先让我们谈谈你的新书《优秀的生活建议》。是什么促使你决定写一本生活建议书?

K.K.: It’s an inadvertent book. Writing a book of advice was never on my bucket list. But I like pithy quotes. When I want to change my own behavior, I need to repeat little behavior-modifying mantras as reminders. I have found that memorable proverbs give me a way to grab hold of lofty advice. So if I can distill a whole book’s worth of advice into a sentence, that gives me the handle for it, to easily bring the lesson forward when needed. With that in mind I started the habit of compressing a lot of useful information into a short memorable tip. Advice is best when directed at a specific person, so I decided to aim my advice at my adult son, who was in his early twenties. Once I started writing tiny bits of advice down for him, I discovered I had a lot to say — as long as I could telegraph it into a tweet. Most of my advice is ancient wisdom, evergreen notions that have been circulating since forever. But I try to put everything into my own words, as few as possible. Most of my writing time on the project was trying to remove words and reduce the advice even further until it is less than 140 characters.

I like an old Irish custom where you give others a present on your birthday. So on my 68th birthday, I gifted 68 short bits of advice to my son, and while I was at it, I shared it with the rest of my extended family and without any expectations, posted it on my blog. The list ricocheted around the internet. So in the following year I started jotting down more adages aimed at my two grown daughters. As I was composing them I kept asking myself a couple of questions: is this advice practical and actionable? Can I stand behind it as true for me? Is this something I wished I had known earlier? If a bit passed these three filters, I’d add it to my list. On my next two birthdays I shared more insights I wished I had known earlier. I must have been getting better because these maxims reached escape velocity and were picked up by bloggers, newsletters and podcasters. They even made it onto the op-ed page of the New York Times.

It’s handy to have blog posts to point to, but I wanted a really easy way to pass these lessons onto a young person or someone young at heart. Thus a small printed book of 450 bits of unsolicited advice that I wished I had known earlier, or Excellent Advice for Living. To be published by Viking/Penguin in May.

K.K.:这是一本无心之作。写一本建议的书从未在我的愿望清单上。但我喜欢简洁的语录。当我想要改变自己的行为时,我需要重复一些行为修改的口头禅作为提醒。我发现,这些记忆深刻的谚语给了我一个抓住高尚建议的方式。因此,如果我能将整本书的建议浓缩成一个句子,那就给了我方便提醒这个教训的把柄。有了这个想法,我开始养成将大量有用的信息压缩成短小易记的提示的习惯。建议最好是针对特定的人,因此我决定将我的建议瞄准我的成年儿子,他当时二十出头。一旦我开始为他写下小小的建议,我发现我有很多话要说——只要我能将其简洁到一条推文的长度。我的大部分建议都是古老的智慧,常青的概念,自古以来一直在流传。但我尽量用我自己的话来表达一切,尽可能少的话语。我在这个项目上的大部分写作时间都是在努力删除多余的话语,将建议进一步减少,直到不到140个字符。

我喜欢一个古老的爱尔兰习惯,在你的生日时给别人一份礼物。因此,在我68岁生日时,我送给了我儿子68个简短的建议,并将其分享给了我的其他亲戚,没有任何期望,并在我的博客上发布了它。这个列表在互联网上流传开来。因此,在接下来的一年里,我开始写下更多的箴言,瞄准我两个成年女儿。当我在创作时,我一直在问自己几个问题:这个建议实用吗?我可以支持它作为我的真实经历吗?这是我早些时候希望自己知道的东西吗?如果一个建议通过了这三个过滤器,我就会将它添加到我的列表中。在我接下来的两个生日里,我分享了更多我希望早些知道的洞见。我一定变得更好了,因为这些格言达到了逃逸速度,并被博客作者、新闻通讯和播客者接受。它们甚至出现在了纽约时报的专栏页面上。

有博客文章可以指向,但我想要一种非常简单的方式将这些教训传递给年轻人或年轻心态的人。因此,我出版了一本小小的印刷书,其中包含450个我希望早些知道的未经请求的建议,或极好的生活建议。这本书将于5月由Viking/Penguin出版。

N.S.: You've spent much of your life as a writer and editor. So your advice should be particularly relevant for me! What are one or two pieces of advice from the book that I should take to heart?

您很大一部分时间都是作家和编辑。所以您的建议对我来说应该尤其相关!您在书中提供的一个或两个建议应该让我深刻领会。

K.K.: Here are a few I learned the hard way:

Most articles and stories are improved significantly if you delete the first page of the manuscript draft. Immediately start with the action.

Separate the processes of creating from improving. You can’t write and edit, or sculpt and polish, or make and analyze at the same time. If you do, the editor stops the creator. While you write the first draft, don’t let the judgy editor get near. At the start, the creator mind must be unleashed from judgment.

To write about something hard to explain, write a detailed letter to a friend about why it is so hard to explain, and then remove the initial “Dear Friend” part and you’ll have a great first draft.

To be interesting just tell your story with uncommon honesty.

K.K.:以下是我通过吃亏学到的几个教训:

大多数文章和故事如果删除手稿草稿的第一页会显著提高质量。 立即从行动开始。

将创作和改进的过程分开。 您无法同时编写和编辑、雕刻和抛光、制作和分析。 如果您这样做,会发现难以继续。 在您编写第一稿时,不要让评判性的编辑接近。在开始时,必须释放创作者的思维而不受判断。

要写关于难以解释的事情,请给朋友写一封详细的信,说明为什么这很难解释,然后删除最初的“亲爱的朋友”部分,您就有了一个很好的第一稿。

要有趣,只需以不寻常的诚实讲述您的故事。

N.S.: Thanks! I will keep those in mind. You're somewhat of a role model for me, since you've managed to weave together surprisingly disparate interests -- technology, environmentalism, foreign cultures -- into a cohesive worldview, mainly through writing and editing, which is something I'd like to do as well. So anyway, let's talk a bit about that. One of your basic ideas is that technology itself makes up a natural system, which you call the technium. When did you first come up with this idea, and what made you think of it?

谢谢!我会记住这些。你对我来说有点像榜样,因为你通过写作和编辑,将技术、环保、外国文化等看似不相关的兴趣融合成了一个有机的世界观。这正是我想做的事情。所以,让我们谈谈这个。你的基本观念之一是,技术本身构成了一个自然系统,你称之为技术体系。你是什么时候想出这个想法的?是什么让你想到它的?

K.K.: First let me define what I mean by the technium. I call our human made system of all technologies working together, the technium. Each technology can not stand alone. It takes a saw to make a hammer and it takes a hammer to make a saw. And it takes both tools to make a computer, and in today’s factory it takes a computer to make saws and hammers. This co-dependency creates an ecosystem of highly interdependent technologies that support each other. The higher the technologies the more intertwined, complex, and codependent they become. At this point in our evolution we need farmers to support indoor plumbing and plumbing to support banks, and banks to enable farmers, and round and round

You might call this network of technologies “culture” because it is the sum of everything that humans make. But the technium is more than just the sum of everything that is made. It differs from culture in that it is a persistent system with agency. Like all systems, the technium has biases and tendencies toward action, in a way that the term “culture” does not suggest. The one thing we know about all systems is that they have emergent properties and unexpected dynamics that are not present in their parts. So too, this system of technologies (the technium) has internal leanings, urges, behaviors, attractors that bend it in certain directions, in a way that a single screwdriver does not. These systematic tendencies are not extensions of human tendencies; rather they are independent of humans, and native to the technium as a whole. Like any system, if you cycle through it repeatedly, it will statistically favor certain inherent patterns that are embedded in the whole system. The question I keep asking is: what are the tendencies in the system of technologies as a whole? What does the technium favor?

This idea kind of arrived from reading the critics of technology, such as Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, or Lewis Mumford, or Langdon Winner. They argued that our human-made artifacts create a deep web of interdependencies which give the technosphere its own agency, and I found their arguments convincing. They see the strength of this system as getting increasingly stronger, with great non-human agency, which I also agree with. But where I depart from the critics is that they are convinced that this network of technologies, this technium, is hostile to both nature and in particular antithetical to us humans, its creators. In fact, in their view, the technium is so antagonistic, and so powerful, yet beyond our control, that we need to dismantle it, or at least diminish it, or unplug it. In the eyes of the Unabomber and other anti-civilizationists, we need to destroy the technium before it destroys us.

On the other hand, I see this technium as an extension of the same self-organizing system responsible for the evolution of life on this planet. The technium is evolution accelerated. A lot of the same dynamics that propel evolution are also at work in the technium. At its core the technium is an ecosystem of inventions capable of evolving entirely new forms of being that wet biology alone can not reach. Our technologies are ultimately not contrary to life, but are in fact an extension of life, enabling it to develop yet more options and possibilities at a faster rate. Increasing options and possibilities is also known as progress, so in the end, what the technium brings us humans is progress.

K.K.:首先,让我定义一下我所说的技术体系。我把我们人类制造的所有技术共同运作的系统称为技术体系。每一种技术都不能单独存在。制作锤子需要用到锯,制作锯也需要用到锤子。而制作计算机需要用到这两种工具,在今天的工厂中,制作锯和锤子需要计算机的支持。这种相互依存创造了高度相互依赖的技术生态系统,它们相互支持。技术越高级,它们就越相互交织、复杂和相互依存。在我们的进化过程中,我们需要农民支持室内管道,需要管道支持银行,需要银行支持农民,周而复始。

你可能会称这个技术网络为“文化”,因为它是人类所创造的一切的总和。但技术体系不仅仅是所有制造物的总和。它与文化的不同之处在于,它是一个具有代理能力的持久系统。像所有系统一样,技术体系具有偏见和行动倾向,这是“文化”一词所不暗示的。我们知道所有系统共同点就是它们有着不在其部分中存在的新兴特性和意想不到的动态。技术体系也有自己的内在倾向、冲动、行为和吸引力,这些因素会使它朝某个方向发展,而单独一把螺丝刀则没有这种倾向。这些系统性倾向不是人类倾向的延伸;相反,它们是独立于人类的,是整个技术体系所固有的。像任何系统一样,如果你反复经过它,它会统计上偏向于嵌入整个系统中的某些固有模式。我一直在问的问题是:技术体系作为一个整体的倾向是什么?技术体系青睐什么?

这个想法是从阅读技术批评家如Ted Kaczynski、Unabomber、Lewis Mumford或Langdon Winner的文章中得出的。他们认为,我们人造的工艺品创建了一种深层次的相互依赖网络,赋予了技术领域自己的代理能力,我认同他们的观点。他们认为,这个系统的强度越来越强,拥有伟大的非人类代理能力,我也同意这一点。但我与批评家的分歧在于,他们相信这个技术网络、这个技术体系对自然界不友好,特别是对我们人类这个创造者来说是对立的。事实上,在他们看来,技术体系是如此敌对、如此强大,而我们无法控制它,以至于我们需要拆除它,或者至少减少它的使用量,或者拔掉它的插头。在反文明主义者如Unabomber看来,我们需要在技术体系毁灭我们之前摧毁它。

另一方面,我认为这个技术体系是同一个自组织系统的延伸,这个系统负责地球上的生命演化。技术体系是演化的加速器。推动演化的许多相同动力也在技术体系中起作用。在其核心,技术体系是一种发明的生态系统,能够演化出完全超越湿生物的新形式。我们的技术最终不是与生命对立的,而是生命的延伸,使其以更快的速度开发出更多的选择和可能性。增加选择和可能性也被称为进步,所以最终,技术体系给我们人类带来的是进步。

N.S.: You talk about the emergent properties of the technium. What are some of these emergent properties? Are we capable of confirming their existence with data and writing down simple, explicable rules that predict the evolution and/or the behavior of the technium itself?

N.S .:你谈到技术体系的新兴属性。这些新兴属性有哪些?我们能够通过数据确认它们的存在并编写简单易懂的规则来预测技术体系自身的演变和/或行为吗?

K.K.: One unexpected emergent property of the technium is that most inventions and innovations are co-invented multiple times, simultaneously and independently. That is, more than one person will honestly invent the next new thing about the same time. This means that the popular image of the lone mad inventor or heroic scientist is just wrong. For instance 23 other inventors created electric incandescent light bulbs prior to Thomas Edison. Edison is renowned primarily because he was the first to figure out the business model of electric lighting. Simultaneous independent invention is the norm, true for minor as well as major leaps like calculus, steam engines and the transistor. Because each and every technology is not a single standalone idea but a web of many ideas, the technium itself emerges as a significant partner in invention. Libraries, journals, communication networks, and the accumulation of other technologies help create the next idea, beyond the efforts of a single individual. If Alexander Graham Bell had not secured the patent for inventing the telephone, Elisha Gray would have gotten it because they both applied for the telephone patent on the same day (Feb 14, 1876). There is plenty of data and confirmation about this emergent phenomenon, and we can predict with pretty good accuracy that lone inventors will become increasingly rare, and that invention and innovation will increasingly operate at a higher institutional level.

To be even more precise, quantitative, and rule-ish, we’d need to have more than a single example of the technium. Right now we have only one technium and so we have an N=1 study, which yields meager reliable rules. But in pre-history, when there was scarce communication between the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, we had a N=5 case. The sequence of inventions on each continent were highly correlated locally, with the order of 60 ancient technologies such as pottery, weaving, and dog domestication appearing in a similar pattern on each separate continent. We also see near-identical parallel inventions of tricky contraptions like slingshots and blowguns. However, because it was so ancient, we don’t have a lot of data for this behavior. What we would really like is to have a N=100 study of hundreds of other technological civilizations in our galaxy. From that analysis we’d be able to measure, outline, and predict the development of technologies. That is a key reason to seek extraterrestrial life.

I think if we did have a robust set of techniums to inspect we’d find emergent phenomena like the rampant replication we see on this planet. At the core of the origin of life, and its ongoing billion-year metabolism, is its ability to replicate and copy information accurately. Life copies itself to live, copies to grow, copies to evolve. Life wants to copy. We could say the same about the technium, particularly the informational technium we are currently swimming in. Anything digital that can be copied, will be copied. To perform any kind of communication, information will be replicated perfectly, again and again. To send a message from one part of the globe to another requires innumerable copies along the route to be made. When information is processed in a computer, it is being ceaselessly replicated and re-copied while it computes. Information wants to be copied. Therefore, when certain people get upset about the ubiquitous copying happening in the technium, their misguided impulse is to stop the copies. They want to stamp out rampant copying in the name of "copy protection,” whether it be music, science journals, or art for AI training. But the emergent behavior of the technium is to copy promiscuously. To ban, outlaw, or impede the superconductivity of copies is to work against the grain of the system. It is a losing game. It’s like trying to work against the propensity of life to replicate. The “rule” then, is to flow with the copies. The prediction would be that innovations, agents, companies, and laws that embrace the easy flow of copies will prevail, while the innovations, agents, companies, and laws that try to thwart liberated ubiquitous copies will ultimately not prevail. This is not the quantitative, precise kind of prediction we’d like to have, but this kind of general emergent trend is the best we’ll do with a sample size of N1.

K.K.:技术体系的一个意外的新兴特性是,大多数发明和创新都是同时和独立地被多个人共同发明的。也就是说,很多人会在差不多同一时间里诚实地发明下一个新事物。这意味着,孤独的疯狂发明家或英雄科学家的普遍形象是错误的。例如,托马斯·爱迪生之前有23位发明家创造了电灯泡。爱迪生之所以著名,主要是因为他第一个想出了电灯的商业模式。同时独立发明是一种常态,这对于微小的跨度和重大的跨度都是真实的,比如微积分、蒸汽机和晶体管。因为每一个技术不是单独的想法,而是许多想法的网络,所以技术体系本身就成为了发明的重要伙伴。图书馆、期刊、通信网络和其他技术的积累帮助创造下一个想法,超越了单个个体的努力。如果亚历山大·格雷厄姆·贝尔没有获得发明电话的专利,伊莉莎·格雷就会获得这个专利,因为他们都在同一天申请了电话专利(1876年2月14日)。有大量的数据和证实这种新兴现象,我们可以预测孤独的发明家将越来越少,发明和创新将越来越在更高的机构层面上运作。

为了更精确、定量和规则化,我们需要不止一个技术体系的例子。现在我们只有一个技术体系,所以我们只有一个N=1的研究,能够获得可靠的规则是有限的。但在史前时期,当美洲、欧洲、亚洲、非洲和澳大利亚之间的通信很少时,我们有一个N=5的案例。每个大陆上的发明顺序在本地高度相关,60种古老技术(如陶器、纺织和驯养狗)的顺序在每个分离的大陆上都呈现出类似的模式。我们还看到了几乎完全相同的平行发明,如弹弓和吹箭。然而,因为它是如此古老,我们没有太多的数据来证明这种行为。我们真正想要的是在我们的银河系中有数百个其他技术文明的N=100的研究。从那个分析中,我们将能够测量、概述和预测技术的发展。这是寻找地外生命的一个关键原因。

我认为,如果我们确实有一个强大的技术体系集合来检验,我们会发现像我们在这个星球上看到的大量复制一样的新兴现象。在生命起源和其持续的亿万年代谢的核心是其准确地复制和复制信息的能力。生命的复制是为了生存,复制是为了成长,复制是为了进化。生命想要复制。我们也可以这样说技术体系,特别是我们目前正在游泳的信息技术体系。任何可以复制的数字都将被复制。为了进行任何形式的通信,信息将被完美地复制,一遍又一遍。要将消息从地球的一部分发送到另一部分,需要制作无数的副本。当信息在计算机中处理时,它正在不断地被复制和再复制,同时计算。信息想要被复制。因此,当某些人对技术体系中的普遍复制感到不满时,他们错误的冲动是停止复制。他们想在“版权保护”的名义下铲除猖獗的复制,无论是音乐、科学杂志还是AI培训的艺术品。但技术体系的新兴行为是不受约束地复制。禁止、取缔或阻碍副本的超导性是逆着系统的潮流而行的。这是一个失败的游戏。这就像试图抵抗生命复制的倾向一样。因此,“规则”是要随着副本的流动。预测是,拥抱易于流动的副本的创新、代理、公司和法律将占优势,而试图阻止解放的无处不在的副本的创新、代理、公司和法律最终将不占优势。这不是我们想要的定量、精确的预测,但这种一般的新兴趋势是我们在N1的样本量下所能做到的最好的。

N.S.: So let's talk about some of the current and near-future effects of the technium on our world. There's currently a big debate about how technology interfaces with the environment. On one side we have degrowthers, who think the environment -- including the climate, but also natural habitats -- can only be preserved by curbing economic growth, and thus see the impact of human technology on the natural world as fundamentally extractive. On the other side are the technologists, who hold that only technological innovation gives us a realistic chance of reducing our environmental footprint and averting truly disastrous climate change. What's your perspective on this debate?

那么让我们来谈一谈技术对我们世界的当前和近期影响。目前有关技术与环境的接口存在着一场激烈的辩论。一方面,我们有“缩退主义者”,他们认为环境(包括气候,但也包括自然栖息地)只有通过遏制经济增长才能得到保护,因此将人类技术对自然界的影响视为根本性的提取。另一方面则是技术专家,他们认为只有技术创新才能给我们减少环境足迹并避免真正灾难性气候变化的现实机会。您对这场辩论有什么看法?

K.K.: There is no question I favor the latter perspective: that while technology has gotten us into this mess (climate change) only technology can get us out of it. Only the technium (our technological system) is “big” enough to work at the global scale needed to fix this planetary sized problem. Individual personal virtue (bicycling, using recycling bins) is not enough. However the worry of some environmentalists is that technology can only contribute more to the problem and none to the solution. They believe that tech is incapable of being green because it is the source of relentless consumerism at the expense of diminishing nature, and that our technological civilization requires endless growth to keep the system going. I disagree.

In English there is a curious and unhelpful conflation of the two meanings of the word “growth.” The most immediate meaning is to increase in size, or increase in girth, to gain in weight, to add numbers, to get bigger. In short, growth means “more.” More dollars, more people, more land, more stuff. More is fundamentally what biological, economic, and technological systems want to do: dandelions and parking lots tend to fill all available empty places. If that is all they did, we’d be well to worry. But there is another equally valid and common use of the word “growth" to mean develop, as in to mature, to ripen, to evolve. We talk about growing up, or our own personal growth. This kind of growth is not about added pounds, but about betterment. It is what we might call evolutionary or developmental, or type 2 growth. It’s about using the same ingredients in better ways. Over time evolution arranges the same number of atoms in more complex patterns to yield more complex organisms, for instance producing an agile lemur the same size and weight as a jelly fish. We seek the same shift in the technium. Standard economic growth aims to get consumers to drink more wine. Type 2 growth aims to get them to not drink more wine, but better wine.

The technium, like nature, excels at both meanings of growth. It can produce more, rapidly, and it can produce better, slowly. Individually, corporately and socially, we’ve tended to favor functions that produce more. For instance, to measure (and thus increase) productivity we count up the number of refrigerators manufactured and sold each year. More is generally better. But this counting tends to overlook the fact that refrigerators have gotten better over time. In addition to making cold, they now dispense ice cubes, or self-defrost, and use less energy. And they may cost less in real dollars. This betterment is truly real value, but is not accounted for in the “more” column. Indeed a tremendous amount of the betterment in our lives that is brought about by new technology is difficult to measure, even though it feels evident. This “betterment surplus” is often slow moving, wrapped up with new problems, and usually appears in intangibles, such as increased options, safety, choices, new categories, and self actualization — which like most intangibles, are very hard to pin down. The benefits only become more obvious when we look back in retrospect to realize what we have gained. Part of our growth as a civilization is moving from a system that favors more barrels of wine, to one that favors the same barrels of better wine.

A major characteristic of sapiens has been our compulsion to invent things, which we have been doing for tens of thousands of years. But for most of history our betterment levels were flatlined, without much evidence of type 2 growth. That changed about 300 years ago when we invented our greatest invention -- the scientific method. Once we had hold of this meta-invention we accelerated evolution. We turned up our growth rate in every dimension, inventing more tools, more food, more surplus, more population, more minds, more ideas, more inventions, in a virtuous spiral. Betterment began to climb. For several hundred years, and especially for the last hundred years, we experience steady betterment. But that betterment — the type 2 growth — has coincided with massive expansion of “moreness.” We’ve exploded our human population by an order of magnitude, we’ve doubled our living space per person, we have rooms full of stuff our ancestors did not. Our betterment, that is our living standards, have increased alongside the expansion of the technium and our economy, and most importantly the expansion of our population. There is obviously some part of a feedback loop where increased living standards enables yearly population increases and more people create the technology for higher living standards, but causation is hard to parse. What we can say for sure is that as a species we don’t have much experience, if any, with increasing living standards and fewer people every year. We’ve only experience increased living standards alongside of increased population.

By their nature demographic changes unroll slowly because they run on generational time. Inspecting the demographic momentum today it is very clear human populations are headed for a reversal on the global scale by the next generation. After a peak population around 2070, the total human population on this planet will start to diminish each year. So far, nothing we have tried has reversed this decline locally. Individual countries can mask this global decline by stealing residents from each other via immigration, but the global total matters for our global economy. This means that it is imperative that we figure out how to shift more of our type 1 growth to type 2 growth, because we won’t be able to keep expanding the usual “more.” We will have to perfect a system that can keep improving and getting better with fewer customers each year, smaller markets and audiences, and fewer workers. That is a huge shift from the past few centuries where every year there has been more of everything.

In this respect “degrowthers” are correct in that there are limits to bulk growth — and running out of humans may be one of them. But they don’t seem to understand that evolutionary growth, which includes the expansion of intangibles such as freedom, wisdom, and complexity, doesn’t have similar limits. We can always figure out a way to improve things, even without using more stuff — especially without using more stuff! There is no limit to betterment. We can keep growing (type 2) indefinitely.

The related concern about the adverse impact of the technology on nature is understandable, but I believe, can also be solved. The first phases of agriculture and industrialization did indeed steamroll forests and wreck ecosystems. Industry often required colossal structures of high-temperature, high pressure operations that did not operate at human or biological scale. The work was done behind foot-thick safety walls and chain link fences. But we have "grown.” We’ve learned the importance of the irreplaceable subsidy nature provides our civilizations and we have begun to invent more suitable technologies. Industrial-strength nuclear fission power will eventually give way to less toxic nuclear fusion power. The work of this digital age is more accommodating to biological conditions. As kind of a symbolic example, the raw ingredients for our most valuable products, like chips, require ultra cleanliness, and copious volumes of air and water cleaner than we’d ever need ourselves. The tech is becoming more aligned with our biological scale. In a real sense, much of the commercial work done today is not done by machines that could kill us, but by machines we carry right next to our skin in our pockets. We continue to create new technologies that are more aligned with our biosphere. We know how to make things with less materials. We know how to run things with less energy. We’ve invented energy sources that reduce warming. So far we’ve not invented any technology that we could not successfully make more green.

We have a ways to go before we implement these at scale, economically, with consensus. And it is not inevitable at all that we will grab the political will to make these choices. But it is important to realize that the technium is not inherently contrary to nature; it is inherently derived from evolution and thus inherently capable of being compatible with nature. We can choose to create versions of the technium that are aligned with the natural world. Or not. As a radical optimist, I work towards a civilization full of life-affirming high technology, because I think this is possible, and by imagining "what could be" gives us a much greater chance of making it real.

K.K .:毫无疑问,我更喜欢后一种观点:虽然技术让我们陷入了这个问题(气候变化),但只有技术才能让我们走出这个问题。只有技术体系(我们的技术系统)才足够“大”,能够在全球范围内解决这个规模庞大的问题。个人的道德美德(骑自行车,使用回收垃圾箱)是不够的。然而,一些环保主义者担心技术只能为问题增添贡献,却无法解决问题。他们认为,技术无法实现绿色环保,因为它是无情消费主义的源头,以牺牲自然为代价,我们的技术文明需要无限增长才能保持系统运转。我不同意。

英语中有一个奇怪而且不太有用的词义混淆:“增长”这个词有两层含义。最直接的含义是增加体积、增加重量、增加数量、变得更大。简而言之,增长意味着“更多”。更多的钱、更多的人、更多的土地、更多的东西。生物、经济和技术系统想要做的基本上都是“更多”:蒲公英和停车场往往会填满所有可用的空地。如果只是这样,我们就有理由担心。但是,“增长”这个词还有另一个同样有效和常见的含义:发展,即成熟、成熟、进化。我们谈论生长、谈论我们自己的个人成长。这种增长不是指增加体重,而是指改善。这是我们所说的进化或发展,或称为第二型增长。它是关于更好地使用相同的原料。随着时间的推移,进化将相同数量的原子排列成更复杂的模式,以产生更复杂的生物体,例如产生一个敏捷的狐猴和一只相同大小和重量的水母。我们寻求在技术体系中实现相同的转变。标准的经济增长旨在让消费者喝更多的葡萄酒。第二型增长的目标是让他们不喝更多的葡萄酒,而是喝更好的葡萄酒。

技术体系就像自然一样,擅长于两种增长方式。它可以快速地生产更多的东西,也可以慢慢地生产更好的东西。在个体、公司和社会方面,我们倾向于支持能够生产更多的功能。例如,为了衡量(从而增加)生产力,我们每年统计制造和销售的冰箱数量。越多越好。但是这种计算往往忽略了冰箱随着时间的推移变得更好的事实。除了制冷,它们现在还可以提供冰块或自动除霜,并且使用的能源更少。而且它们可能在实际美元中的成本更低。这种改善是真正的价值,但没有计入“更多”列中。事实上,新技术带来的我们生活中的改善的巨大部分很难衡量,即使它们看起来很明显。这种“改善剩余”通常是缓慢的,与新问题密切相关,并且通常出现在无形中,例如增加的选择、安全、选择、新类别和自我实现——这些与大多数无形资产一样,都很难确定。只有在回顾过去时,我们才会意识到我们所获得的好处更加明显。作为我们文明的一部分,我们正在从一个偏爱更多酒桶的系统转向一个偏爱相同酒桶更好的系统。

Sapiens的一个主要特征是我们发明事物的冲动,这是我们已经做了几万年的事情。但是在大部分历史中,我们的改善水平一直停滞不前,没有太多第二型增长的证据。大约300年前,当我们发明了我们最伟大的发明——科学方法时,情况发生了改变。一旦我们掌握了这种元发明,我们就加快了进化的速度。我们在每个维度上提高了增长率,在良性循环中发明了更多的工具、更多的食物、更多的盈余、更多的人口、更多的思想、更多的发明。改善开始上升。几百年来,尤其是在过去一百年中,我们经历了稳定的改善。但是这种改善——即第二型增长——与“更多”的大规模扩张同时发生。我们把人类的人口数量增加了一个数量级,我们将每个人的生活空间翻了一番,我们拥有的东西比我们的祖先多。我们的改善,即我们的生活水平,随着技术体系和经济的扩张,特别是人口的扩张而提高。显然,有一部分反馈循环,即提高生活水平使每年的人口增加,并且更多的人创造了提高生活水平的技术,但是因果关系很难解释。我们可以毫不怀疑地说,作为一个物种,我们没有太多的经验,如果有的话,就是每年生活水平提高,人口却更少。我们只有在人口增加的同时提高生活水平的经验。

由于它们在代际时间上运行,因此人口统计变化会缓慢展开。检查当今的人口动力学,很明显,人类人口正在全球范围内迎来逆转。在约2070年达到人口峰值后,这个星球上的总人口将开始逐年减少。到目前为止,我们尝试的所有方法在本地都没有扭转这一趋势。个别国家可以通过移民从彼此那里偷走居民来掩盖这种全球性的下降,但对于我们的全球经济而言,全球总量很重要。这意味着我们必须想办法将更多的第一型增长转化为第二型增长,因为我们将无法继续扩张通常的“更多”。我们将不得不完善一个系统,使其能够随着每年的客户、更小的市场和观众以及更少的工人而不断改进和变得更好。这是过去几个世纪以来的一个巨大转变,因为每年都有更多的一切。

在这方面,“退化论者”是正确的,因为大规模增长存在限制——人类的消失可能是其中之一。但是他们似乎不理解,包括自由、智慧和复杂性扩展在内的进化增长并没有类似的限制。即使不使用更多的东西,我们总是可以想出改进事物的方法——尤其是不使用更多的东西!改善没有限制。我们可以无限期地保持增长(第二型)。

与技术对自然的不利影响有关的担忧是可以理解的,但我认为也可以解决。农业和工业化的第一阶段确实压垮了森林并破坏了生态系统。工业往往需要高温、高压操作的巨大结构,这些操作不是在人类或生物尺度上运作的。工作是在安全墙和链网栏杆后完成的。但是我们已经 “长大了”。我们已经意识到自然对我们文明提供的不可替代的补贴的重要性,并开始发明更适合的技术。工业级核裂变动力将最终让位于更少有毒的核聚变动力。数字时代的工作更符合生物条件。作为一种象征性的例子,我们最有价值的产品的原材料需要超级清洁,并且需要比我们自己需要的更多的空气和水。技术正在与我们的生物尺度越来越相符。在实际意义上,今天完成的大部分商业工作都不是由可能杀死我们的机器完成的,而是由我们随身携带的机器完成的。我们继续创造与我们的生物圈相一致的新技术。我们知道如何使用更少的材料制造物品。我们知道如何使用更少的能量来运行事物。我们发明了减少变暖的能源来源。到目前为止,我们还没有发明任何一种技术,我们无法成功地使其更加环保。

在实现这些技术的规模化、经济化和共识方面,我们还有很长的路要走。我们也不可能不避免地获得政治意愿来做出这些选择。但是重要的是要意识到,技术体系本质上并不与自然相悖;它本质上来源于进化,因此本质上能够与自然兼容。我们可以选择创建与自然世界相一致的技术。或不。作为一个激进的乐观主义者,我致力于创造充满生命力的高技术文明,因为我认为这是可能的,并且通过想象“可能性”,我们实现它的机会更大。

N.S.: I really like that vision a lot. You and I are quite closely aligned on our basic techno-optimism, our view of growth, and our concept of the relationship between human civilization and nature. But I'd like to try to challenge this optimism a little bit. Since around 2010, there have been increasing concerns about the direction the technium has taken us -- toward smartphones that absorb all our attention and take us out of the world and foster loneliness, toward social networks that sow sociopolitical discord and create feelings of personal inadequacy. Do you think innovation took something of a wrong turn in the 2010s, or are these problems overstated?

我非常喜欢这个愿景。你和我在基本技术乐观主义、增长观和人类文明与自然关系的概念上非常接近。但我想试着挑战一下这种乐观主义。自2010年左右以来,人们对技术的发展方向越来越担忧——智能手机吸引了我们所有的注意力,让我们远离世界,培养了孤独感;社交网络播下了社会政治上的不和谐,让人感到个人的不足。您认为创新在2010年代走了弯路,还是这些问题被夸大了?

K.K.: These problems are overstated. The thing to remember when evaluating new technologies is we have to always ask “compared to what?.” Mercury-based dental fillings statistically caused some harm, but compared to what? Compared to cavities, they were a miracle. We tend to give existing technologies a pass from the degree of scrutiny we give new technologies. Social media can transmit false information at great range at great speed. But compared to what? Social media's influence on elections from transmitting false information was far less than the influence of the existing medias of cable news and talk radio, where false information was rampant. Did anyone seriously suggest we should regulate what cable news hosts or call in radio listeners could say? Bullying middle schoolers on social media? Compared to what? Does it even register when compared to the bullying done in school hallways? Radicalization on YouTube? Compared to talk radio? To googling?

The complexity of social media is akin to biology. It is not a coincidence that we speak of things going viral. Figuring out what is going on with these new platforms, what is harmful, what is beneficial, is as challenging as determining what is best for our health. Human bodies have so many interacting variables, all difficult to isolate, that we can’t rely on a single or even a few studies to determine our best health practices. Initial, honest, well-crafted medical studies are often proven wrong, sometimes embarrassingly wrong, many studies later. In fact it may take hundreds of studies before we can say a result is “true." Social media is equally complex, with even more variables, and it is still an infant. We are trying to evaluate a baby that is roughly 250 months old, and hoping to predict what it will be good for when it grows up.

A further complication is that we are judging a class of technologies based on what kids do with them. Kids are inherently obsessive about new things, and can become deeply infatuated with stuff that they outgrow and abandon a few years later. So the fact they may be infatuated with social media right now should not in itself be alarming. Yes, we should indeed understand how it affects children and how to enhance its benefits, but it is dangerous to construct national policies for a technology based on the behavior of children using it.

Similarly, we should be wary of evaluating a technology within only one culture. So far, we are extremely biased because we have examined social media primarily in the US. There is little research on the effects — plus or minus — on users in other cultures. Since it is the same technology, inspecting how it is used in other parts of the world would help us isolate what is being caused by the technology and what is being caused by the peculiar culture of the US.

There are surely new problems generated by social media. We can not use something for hours a day, every day, and have it not affect us. We have hints, but don’t really know. As we discover how it works, a wise society would modulate how this technology is used — by adults and children. As we begin to understand its tendencies, harms and benefits, we can devise incentives to continually re-design the tech to enhance democracy and well-being. All this must be done on the fly, in real time, because what we have learned over the past 100 years is that we can’t figure out, and can’t predict, what technologies will be good for simply by thinking and talking about them. New technologies are so complex they have to be used on the street in order to reveal their actual character. We are likely to guess wrong at first, as we have been wrong in the past when trying to guess what a new technology meant. We can laugh now at the moral panics over the degrading nature of novels, cinema, sports, music, dancing, TV, and comic books (the latter two prohibited in our house when I was growing up), but we know prohibitions never work in the long term. We should engage with social media, because we can only steer technologies while we engage them. Without engagement we don’t get to steer.

这些问题被夸大了。在评估新技术时,我们必须时刻问“与什么相比?”虽然基于汞的牙科填充材料在统计上造成了一些伤害,但与什么相比呢?与龋齿相比,它们是一种奇迹。我们倾向于对现有技术给予相对宽松的审查,而对新技术给予更高的审查度。社交媒体可以以很高的速度传播虚假信息。但与什么相比呢?社交媒体传播虚假信息对选举的影响远远不如有线电视新闻和脱口秀电台。在那里,虚假信息猖獗。有人曾认真建议我们对有线电视新闻主持人或打电话给电台节目的听众说什么进行管制吗?社交媒体上欺负中学生?与什么相比呢?与在学校走廊里进行的欺负相比,它甚至没有什么影响?YouTube上的激进化?与电台呢?与谷歌搜索呢?

社交媒体的复杂性类似于生物学。我们讲某些东西会“病毒式传播”,这不是巧合。了解这些新平台发生了什么、什么是有害的、什么是有益的,就像确定我们的健康最佳实践一样具有挑战性。人体有太多相互作用的变量,所有这些变量都难以隔离,我们不能依靠单个或甚至少量的研究来确定我们的最佳健康实践。最初、诚实、精心制作的医学研究往往被证明是错误的,有时候尴尬地错误,许多研究后才被证明是“正确”的。事实上,可能需要进行数百 项研究才能说一个结果是“正确”的。社交媒体同样复杂,有更多的变量,而且它还是一个婴儿。我们正试图评估一个大约有250个月大的婴儿,希望能预测它长大后会有什么用处。

更进一步的是,我们是根据孩子的使用来评估一类技术的。孩子们在新事物上天生就是痴迷的,他们可能会对他们长大后会放弃的东西深深地着迷。因此,他们现在对社交媒体着迷,本身并不是令人担忧的。是的,我们确实应该了解它如何影响儿童以及如何增强它的好处,但是基于儿童使用它的行为来构建技术的国家政策是危险的。

同样地,我们应该警惕仅在一个文化中评估技术。到目前为止,我们非常偏向于在美国主要研究社交媒体。在其他文化中使用它的用户的影响 - 正面或负面 - 很少有研究。由于它是同样的技术,检查它在世界其他地方的使用方式将有助于我们隔离技术所引起的是什么,以及美国独特文化所引起的是什么。

当然,社交媒体肯定会产生新问题。我们不能每天使用几小时,每天使用它而不受影响。我们有一些暗示,但并不真正知道。随着我们发现它的工作方式,明智的社会将调节成人和儿童使用这种技术的方式。随着我们开始理解它的倾向、危害和好处,我们可以制定激励措施,不断重新设计技术,以增强民主和福祉。所有这些都必须在现实时间内实时完成,因为我们在过去的100年里学到的是,我们不能仅仅通过思考和谈论来确定什么技术是好的,也不能预测它们的作用。新技术非常复杂,必须在街头使用才能揭示它们的实际特征。我们很可能一开始猜错,就像过去猜错新技术的意义一样。我们现在可以嘲笑小说、电影、体育、音乐、舞蹈、电视和漫画书的道德恐慌(后两者在我成长的时候被禁止),但我们知道禁令从长远来看永远不会生效。我们应该与社交媒体互动,因为只有在我们参与其中时,我们才能引导技术的发展。

N.S.: When you say "only we can steer technologies", who does the "steering"? Should government be regulating new technologies more heavily, and if so, how? It seems hard for users themselves -- ourselves! -- to steer these technologies. I've been a heavy Twitter user for years, but I've never managed to do much about its tendency toward misinformation and performative, attention-seeking aggression. No one else has either. How can we steer big platforms?

当您说“只有我们可以引领技术”时,谁来“引领”?政府是否应更严格地监管新技术,如果是,该如何实施?似乎很难让用户自己引领这些技术。我多年来一直是Twitter的重度用户,但我从未能够有效地解决其虚假信息和表现性、追求关注的攻击倾向。其他人也没有。我们如何引导大型平台?

K.K.: There are 3 levels of steerage. Level 1, individually we (you) ARE steering Twitter when you decide to mute or not to mute, or ban or not ban. You are voting what you think is important by using it. Or some people vote by not using it. You don’t notice what difference you make because of the platform's humongous billions-scale. In aggregate your choices make a difference which direction it — or any technology — goes. People prefer to watch things on demand, so little by little, we have steered the technology to let us binge watch. Streaming happened without much regulation or even enthusiasm of the media companies. Street usage is the fastest and most direct way to steer tech.

Level 2, is regulation by governments. This can work, and is often necessary to steer. The challenge is premature regulation. The panic cycle for tech begins on the first bit of news about possible harms to anyone, and first response is a call to regulate. But as we just discussed, because it’s a newborn, it is easy — if not certain — that our first impressions about the tech are wrong, and thus early regulations often tend to brake more than steer. We have some good case examples of regulating tech in the right direction. We steered DDT away from being used as a plantation-scale pesticide (poisoning entire wildlife ecosystems), and redirected to be used judiciously, carefully, in small amounts in villages to eliminate mosquito borne malaria, saving the lives of many millions with minimum effect on ecosystems. That took years to accomplish, but the evidence was vivid. We should require more than precautionary type of evidence in order to use regulation to steer.

The third level of steerage is through innovation and entrepreneurship. When new problems are seen, new solutions are invented. Sometimes engineers in the host companies offer technical remedies, or shift directions. Often times solutions come from startups outside. Occasionally new directions are developed by the customers themselves. Vibrators instead of the cacophony of ringing bells on cell phones is one example of a marketplace technological solution. The marketplace needs regulation to keep it level, clean, optimal, and fertile for innovations to flourish. This is probably the more important role for regulation in steering.

It’s a messy process. And as messy as it has been to steer social media, it will be even messier to steer AIs and genetic engines, principally because they are so close to our identity as human and because we are so ignorant of what humans are good for. Consensus of a preferred direction will be very slow in coming. And slow should be mandatory regulation.

KK:有三个层次的操纵。第一层,当你决定是否静音或封禁时,你个人就在操纵 Twitter。你使用它来表达你认为重要的问题,或者有些人通过不使用它来表达意见。由于这个平台庞大的规模,你不会注意到你所做出的差异。但是,总体上你们的选择将决定它或任何技术的方向。人们喜欢随需而变地观看事物,所以我们逐渐将技术引向了让我们能够连续观看的方向。流媒体的发展没有受到太多规制,甚至没有得到媒体公司的热情支持。街头使用是引领科技的最快、最直接的方式。

第二层是政府的规制。这可能是有效的引导方式,通常也是必要的。挑战在于过早的规制。科技恐慌循环始于第一条关于可能对任何人造成伤害的新闻,而第一反应就是呼吁加强规制。但正如我们刚刚讨论的,由于它是新生事物,我们对科技的第一印象往往是错误的,因此早期规制往往会制约新技术而不是将它向好的方向引导。我们有一些很好的案例可以证明,正确的技术规制可以使科技的发展方向得到引领。我们把 DDT 从一种种植规模的杀虫剂转变为谨慎、小心地在村庄中使用的少量药剂,以消灭蚊媒疟疾,拯救了数百万人的生命,并对生态系统的影响最小。这需要数年时间才能完成,但证据是明显的。我们应该要求更多的证据来使用规制来引导。

第三层是通过创新和企业家精神来引领。当出现新问题时,就会有新解决方案被发明出来。有时,主机公司的工程师提供技术解决方案或改变方向。通常,解决方案来自于外部的初创企业。偶尔,顾客自己也能开发出新的方向。在手机上使用振动器而不是喧闹的铃声就是一个市场技术解决方案的例子。市场需要规制来保持平衡、清洁、最佳和有利于创新的发展。这可能是规制在引导方面的更重要的作用。

这是一个混乱的过程。虽然引领社交媒体的过程很混乱,但是引领人工智能和基因引擎将会更加混乱,主要因为它们与我们作为人类的身份非常接近,并且我们对人的价值还非常无知。达成对首选方向的共识将非常缓慢。缓慢应成为强制性规制。

N.S.: In fact, that's a good segue into the topic of AI, which of course everyone is talking about, given the recent success of chatbots and AI art programs. Where do you land on the spectrum of enthusiasm. Does this new technology change everything, or is it overhyped? What do you expect to change as a result of the new efflorescence of AI? Will the relationship between humanity and the technium fundamentally alter?

实际上,这是一个很好的过渡到AI话题的方法,当然,考虑到聊天机器人和AI美术程序的最近成功,每个人都在谈论它。您对热情的谱系有何看法?这项新技术是否改变了一切,或者被过度宣传了?您期望由于AI的新繁荣而发生什么变化?人类与技术之间的关系是否会根本性地改变?

K.K.: Despite the relentless hype, I think AI overall is underhyped. The long-term effects of AI will affect our society to a greater degree than electricity and fire, but its full effects will take centuries to play out. That means that we’ll be arguing, discussing, and wrangling with the changes brought about by AI for the next 10 decades. Because AI operates so close to our own inner self and identity, we are headed into a century-long identity crisis.

This span is particularly notable because we have been discussing the effects of AI for 100 years already. In fact, never before have humans so thoroughly rehearsed something as far ahead as AI. Long before it arrives, we’ve been imagining its pros and cons, and trying to anticipate it for several generations. This serious rehearsal is an improvement in our culture, and a pattern we should continue for other technologies like genetic engineering, the metaverse, and so on. The upside to a long rehearsal is that upon arrival, we should not be too surprised. The downside to a long rehearsal is that there are more ways something goes wrong than right, and we’ve had time to think of all of the horrible stuff, so that the positive conjectures feel mythical and unreal.

But now, here are chatbots, commercially available. However, in 30 years we will look back to 2023 and everyone then will agree that while something is happening with artificial smartness, we do not have anything like AI now. What we tend to call AI, will not be considered AI years from now. One useful corollary of this is that from the perspective of looking back 30 years hence, there are no AI experts today. This is good news for anyone starting out right now, because you have as much chance as anyone else of making breakthroughs and becoming the reigning experts.

Nonetheless, right now machine learning is overhyped. It is not sentient, and not as smart as it seems. What we are discovering is that many of the cognitive tasks we have been doing as humans are dumber than they seem. Playing chess was more mechanical than we thought. Playing the game Go is more mechanical than we thought. Painting a picture and being creative was more mechanical than we thought. And even writing a paragraph with words turns out to be more mechanical than we thought. So far, out of the perhaps dozen of cognitive modes operating in our minds, we have managed to synthesize two of them: perception and pattern matching. Everything we’ve seen so far in AI is because we can produce those two modes. We have not made any real progress in synthesizing symbolic logic and deductive reasoning and other modes of thinking. It is those “others” that are so important because as we inch along we are slowly realizing we still have NO IDEA how our own intelligences really work, or even what intelligence is. A major byproduct of AI is that it will tell us more about our minds than centuries of psychology and neuroscience have.

K.K.:尽管AI一直被炒作,但我认为它总体上被低估了。长期来看,AI的影响将比电力和火灾对我们的社会产生更大的影响,但其全部效应需要几个世纪才能显现。这意味着我们将在未来10年中就由AI带来的变化进行争论、讨论和斗争。由于AI的作用如此接近我们自身的内在自我和身份,我们将进入一个持续一个世纪的身份危机。

这个时期特别值得注意,因为我们已经讨论了100年的AI影响。事实上,人类从来没有像对AI这样从很远讨论一件事情。在它到来之前,我们已经想象了它的利弊,并有几代人试图预测它。这种认真的准备是我们文化的一种改进,也是一个我们应该为其他技术如基因工程、元宇宙等继续保持的模式。长时间的排练的好处是,一旦到达,我们不应该太惊讶。长时间排练的缺点是,事情出错的方式比正确的方式更多,而我们已经有时间想到所有可怕的事情,因此积极的猜测感觉像神话般不真实。

但现在,在商业上已经有聊天机器人可用。然而,30年后,我们将回顾2023年,每个人都会同意,虽然人工智能的智能正在发生变化,但我们现在没有类似人工智能的东西。我们倾向于称之为人工智能的东西,未来几年将不被认为是人工智能。这个有用的推论是,从回顾30年前的角度来看,今天没有人工智能专家。这对于现在开始的任何人来说都是好消息,因为你有与其他人一样的机会取得突破并成为主宰专家。

然而,目前机器学习被过度炒作。它不是有感觉的,也没有看起来那么聪明。我们正在发现,我们作为人类所做的许多认知任务比我们想象的更愚蠢。下棋比我们想象的更机械化。下围棋比我们想象的更机械化。绘画和创造性的创作比我们想象的更机械化。甚至用单词写一段话也比我们想象的更机械化。到目前为止,在我们的大脑中可能有十几种认知模式中,我们已经成功合成了其中的两种:感知和模式匹配。我们在人工智能中看到的一切都是因为我们能够产生这两种模式。我们在合成符号逻辑、演绎推理和其他思维模式方面没有取得任何真正的进展。正是这些“其他”非常重要,因为当我们一步步前进时,我们慢慢意识到我们仍然不知道我们自己的智力是如何运作的,甚至不知道智力是什么。人工智能的一个主要副产品是它将告诉我们比心理学和神经科学几个世纪还要多的关于我们的思维的信息。

There are books full of lessons waiting to be said about about AI as it is being born, so let me state just a few provocative points about what I expect:

We should prepare ourselves for AIs, plural. There is no monolithic AI. Instead there will be thousands of species of AIs, each engineered to optimize different ways of thinking, doing different jobs (better than a general AIs could do). Most of these AIs will be dumbsmarten: smart in many things and stupid in others. Expect frustration about how stupid they can be while being so smart.

Theoretically any computer can emulate any other computer, but in practice it matters what substrate a computer runs on. No matter how fast or “smart” an AI may be, as long as it runs on silicon it will remain an alien. Its intelligence will be brilliant, but alien. Its humor will be sharp, but a little off. Its creativity will be intense, but a little otherworldly. The best framework for understanding complex AIs is to think of them as artificial aliens. Think of a robot Spock, super smart, but not quite human.

Consciousness is a liability and not an asset in an AI. It is distracting and dangerous. We want our AIs to just drive, and not get anxious. Many expensive AIs will be advertised as “consciousness-free.”

The relationship AIs will have with us will tend towards being partners, assistants, and pets, rather than gods. This first round of primitive AI agents like ChatGPT and Dalle are best thought of as universal interns. It appears that the millions of people using them for the first time this year are using these AIs to do the kinds of things they would do if they had a personal intern: write a rough draft, suggest code, summarize the research, review the talk, brainstorm ideas, make a mood board, suggest a headline, and so on. As interns, their work has to be checked and reviewed. And then made better. It is already embarrassing to release the work of the AI interns as is. You can tell, and we’ll get better at telling. Since the generative AIs have been trained on the entirety of human work — most of it mediocre — it produces “wisdom of the crowd”-like results. They may hit the mark but only because they are average.

Because AIs are being trained on average human work, they exhibit the biases, prejudices, weaknesses, and vices of the average human. But we are not going to accept that. Nope. We want the ethics and values of AIs to be better than ours! They have to be less racist, less sexist, less selfish than we are on average. It is NOT difficult to program in ethical and moral guidelines into AIs — it is just more code. The challenge is that we humans have no consensus on what we mean by “better than us,” and exactly who “us” is. The problem is not the AIs. The problem is that the AIs have illuminated our own shallow and inconsistent ethics — even at our best. So making AIs better than us is a huge project.

I am not aware of any person who has lost their job to an AI so far. There may be a few professions — like the person paid to transcribe a talk into text — that will go away, but most jobs will shift their tasks to accommodate the emerging power of AI. Most of the worry about AI unemployment so far is third-person worry — people imagine some other person getting fired, not themselves.

Different AIs will have different personalities. We already see this with image generators; some artists prefer working with one rather than another. It takes an extremely close intimacy to get your intern AI to help you produce great work. Some people are 10x and 100x better than others with these tools. They have become AI whisperers. Other people are repelled by this alienness and want nothing to do with it. That is fine. But 90% of AIs will never be encountered by anyone. That is because the bulk of AIs will run hidden in back offices. They will metaphorically reside in the walls so to speak, like plumbing and electrical wires -- vital but out of mind. This invisibility is the mark of the most successful technologies — to be ubiquitous but not seen.

Before this becomes a book, I’ll stop there.

有关人工智能的教训已经有很多本等待被说出来,所以让我就我所期望的提出一些具有挑衅性的观点:

我们应该为多种人工智能做好准备。并不存在一个统一的人工智能,相反,将会有成千上万种人工智能物种,每一种都被设计优化不同的思维方式,执行不同的工作(比普通人工智能做得更好)。这些人工智能中的大多数会是“聪明笨蠢”的,在很多方面很聪明,但在其他方面很傻。预计会有一些挫败感,因为尽管它们很聪明,但它们也可能很愚蠢。

理论上,任何计算机都可以模拟任何其他计算机,但实际上,计算机运行的基质很重要。无论人工智能有多快、多“聪明”,只要它运行在硅基质上,它将始终是外来的。它的智慧将是卓越的,但很奇特。它的幽默感将是犀利的,但有点偏差。它的创造力将是强烈的,但有点来自异世界。理解复杂人工智能的最佳框架是将它们视为人造外星人。想象一下机器人斯波克(Spock),超级聪明,但并非完全像人类。

意识对于人工智能来说是一种负担而不是资产。它会分散注意力,也会带来危险。我们希望我们的人工智能只是驱动,而不会感到焦虑。许多昂贵的人工智能将被宣传为“无意识”的。

人工智能与我们的关系会倾向于成为合作伙伴、助手和宠物,而不是神。这一轮原始的人工智能代理,如ChatGPT和Dalle,最好被视为通用实习生。似乎今年第一次使用它们的数百万人正在使用这些人工智能来做他们如果有个人实习生会做的事情:写草稿、建议代码、总结研究、审查演讲、头脑风暴、制作心情板、建议一个标题等等。作为实习生,他们的工作必须被检查和审核。然后让它更好。将AI实习生的工作原封不动地发布出去已经很尴尬了。你能看出来,而且我们会越来越擅长看出来。由于生成人工智能已经在人类工作的全部范围内进行了培训——其中大部分是平庸的——因此它产生了“群众的智慧”式的结果。他们可能会击中要害,但这只是因为它们是平均水平。

由于人工智能正在接受平均人类工作的培训,因此它们表现出平均人类的偏见、偏见、弱点和恶习。但我们不会接受这一点。不会。我们希望人工智能的道德和价值观比我们更好!他们必须比我们平均水平的种族更不种族主义、更少性别歧视、更少自私。将伦理和道德准则编程到人工智能中并不困难——这只是更多的代码。挑战在于我们人类对于“比我们更好”是什么意思以及“我们”到底是谁没有共识。问题不在于人工智能,而在于人工智能已经照亮了我们自己肤浅而不一致的伦理——即使在我们最好的时候也是如此。因此,让人工智能比我们更好是一个巨大的项目。

我不知道有没有人失去工作机会,被人工智能所取代。可能会有一些职业——比如被付费将讲话转录成文本的人——将会消失,但大多数工作将调整他们的任务来适应人工智能的新兴力量。到目前为止,大多数人对于人工智能导致失业的担忧都是第三人称的——人们想象其他人被解雇,而不是自己。

不同的人工智能将有不同的个性。我们已经在图像生成器上看到了这一点;一些艺术家更喜欢使用其中一种。需要极其密切的亲密关系才能让你的实习生人工智能帮助你产生优秀的作品。有些人用这些工具比其他人好10倍甚至100倍。他们已经成为人工智能的耳语者。其他人则被这种异类所排斥,不想与之有任何关系。这很好。但90%的人工智能将永远不会被任何人遇到。这是因为大部分人工智能将在后台运行而被隐藏起来。它们将象征性地驻留在墙壁中,就像管道和电线——重要但被忽视。这种隐形是最成功的技术标志——无处不在但不受关注。

在这成为一本书之前,我就停在这里。

N.S.: I share your optimism about AI. But let's briefly talk about the times when futurism fails. Two years ago, a lot of people in the tech world were talking breathlessly about -- and throwing very large amounts of money at -- "web3", a catch-all name for crypto stuff. We heard wide-eyed tales about how crypto would usher in an era of permissionless commerce, a new ownership society, financial independence, a new efflorescence of online creativity. Instead, essentially everything created in that crypto boom turned out to be either a Ponzi scheme, a pump-and-dump scam, or simply wildly overoptimistic. To cite a less dramatic example, the gig economy was supposed to revolutionize human labor and income and land use, but its impact, while real, has been much more modest than people expected. Is there any systematic reason these technological visions fell short? Is it possible to tell in advance what new limbs our technium will see fit to graft onto its body? Or is it just a matter of taking a lot of shots on goal and seeing what works?

我和你一样对AI充满乐观。但是让我们简要谈谈未来主义失败的时候。两年前,许多科技界人士热烈地谈论着“web3”,这是一个包罗万象的加密货币概念。我们听到了有关加密货币将引领无许可商业、新的所有权社会、财务独立、在线创造力的新时代的令人瞪大眼睛的故事。然而,实际上在加密货币繁荣期间创造的几乎所有东西都被证明是庞氏骗局、短线操作骗局或简单地过度乐观。作为一个不那么戏剧性的例子,零工经济本应该革命性地改变人类劳动、收入和土地利用,但它的影响,虽然真实,但比人们预期的要小得多。这些技术愿景缺乏系统性的原因吗?有可能事先知道我们的技术将会植入哪些新的肢体吗?还是只是尽可能地投入大量的资金,然后看看哪些有效呢?

K.K.: The baseball oracle once said: predictions are hard to make, especially about the future. I think it is hard enough to predict the present. If we could predict the present, we’d be half done. Most of my work is trying to see what is actually happening right now.

Futurism fails all the time, but I actually think we are getting better at it. For one, we tend to over estimate change in the short term, and underestimate it over the longer term, and I see evidence of us beginning to learn that lesson and shift our expectations. Two, we’ve learned to expect that even nice technologies bite back. Now from the get-go we assume there will be significant costs and harms of anything new, which was not the norm in my parent's generation. Scenario planning, once esoteric, is now standard corporate planning procedure. Scenarios are less about predicting exactly what will happen and more about imagining the range of possible futures so that you are not surprised when one of them happens, and you can use the scenarios to generate contingency plans — what would we do if the world headed in this direction? This is a giant step forward in managing the future.

This does not prevent a future fail like what happened with crypto. The astronomical volume of money and greed flowing through this frontier overwhelmed and disguised whatever value it may have had. If you prohibited the mention of “money”, “making money” or “saving money” from any discussion of crypto, it was always a very short conversation. I suspect there are some powerful ideas and tech possible using blockchain, but these value propositions are not going to show up until crypto is seen as an expense instead of a way of making money. It has to be valuable while it loses money, and that has not happened yet.

I think the fail of crypto is less a failure of futurism than a flop in culture in general. When I first experienced virtual reality in 1989, I felt sure the world would change in the next 5 years. It’s been 30 years now and the state of VR is about the same. I was part of a small group of techno-enthusiasts who thought believable VR was imminent, and got it wrong. What’s been different about crypto is that the main boosters have not been a small group of techno-enthusiasts. Rather crypto has been promoted sky high by athletes, celebrities, shoe companies, day traders, politicians, and hustlers. Half of the usual technology evangelists, like myself, have been silent on crypto, or openly skeptical of it. For every tech promoter of crypto there’s been a very educated tech criticism of it. And I don’t mean the usual tech criticism of “this is bad,” I mean the tech criticism of “this does not work.” (I would cautiously add the word “yet”.) So to half of the tech and futurist community, it is only a half-fail. And taking to heart the lesson #1 above, crypto still has potential to be revolutionary in the long run. The sweet elegance of blockchain enables decentralization, which is a perpetually powerful force. This tech just has to be matched up to the tasks — currently not visible — where it is worth paying the huge cost that decentralization entails. That is a big ask, but taking the long-view, this moment may not be a failure. I would say the same about the gig economy — let’s give it more time to judge; it’s barely been around 5,000 days.

K.K.:棒球神预言说过:预测很难,特别是关于未来的预测。我认为预测现在已经很难了。如果我们能预测现在,我们就完成了一半工作。我的大部分工作是试图了解当前实际发生的事情。

未来主义经常失败,但我认为我们越来越擅长预测未来。首先,我们往往高估短期内的变化,低估长期内的变化,我看到我们开始学习这个教训并调整我们的期望。其次,我们已经学会了预期即使是好的技术也有负面影响。现在从一开始,我们就假定任何新的事物都会有显著的成本和危害,这在我父母的一代人中不是常态。情景规划曾经是玄学的,现在已成为标准的公司规划程序。情景规划不是准确预测会发生什么,而是想象可能的未来范围,以便当其中一个发生时不会感到惊讶,并可以使用情景规划生成应急计划——如果世界朝这个方向发展,我们该怎么办?这是管理未来的重大进步。

这并不能防止未来的失败,就像加密货币的失败一样。通过这一前沿流动的巨额资金和贪欲,淹没并掩盖了它可能具有的任何价值。如果在任何加密货币的讨论中禁止提及“钱”、“赚钱”或“省钱”,那么这将是一个非常短暂的对话。我怀疑使用区块链可能有一些强大的思想和技术,但除非将加密货币视为一种费用而不是赚钱的方式,否则这些价值主张不会出现。它必须在亏损的同时具有价值,而这还没有发生。

我认为加密货币的失败不是未来主义的失败,而是文化总体的失败。1989年我第一次体验虚拟现实时,我确信世界将在接下来的5年内发生改变。现在已经过去了30年,VR 的状态几乎没有变化。我是一小群技术热情者中的一员,他们认为可信的虚拟现实即将到来,并被证明是错误的。不同之处在于,加密货币的主推者不是一小群技术热情者。相反,运动员、名人、鞋类公司、日间交易者、政治家和骗子将加密货币推到了天上。一半的技术布道者(包括我自己)对加密货币保持沉默或公开怀疑。对于每个推动加密货币的技术布道者,都有一个非常受过教育的技术批评者。我不是指“这是坏的”的常规技术批评,而是指“这不起作用”的技术批评。(我谨慎地加上“尚未”这个词。)因此,对于技术和未来主义社区的一半人来说,这只是半个失败。根据上面的教训#1,长期来看,加密货币仍有可能具有革命性。区块链的甜美优雅实现了去中心化,这是一个永久强大的力量。这项技术只是需要与任务相匹配,而目前这些任务尚不可见,它是否值得支付分散的巨大成本。这是一个很大的要求,但从长远来看,这一时刻可能不是一个失败。我对零工经济也持同样的看法——让我们给它更多的时间来判断;它只存在了不到5000天。

N.S.: I usually close these interviews by asking what someone is working on right now. In your case, I feel like I'll just read whatever it is when it comes out! So today I'll switch it up a bit. What do you think young people should be working on right now? What's exciting, new, and important in the world of 2023?

我通常在采访结束时会问对方正在从事什么工作。在你的情况下,我感觉当作品发布时我会读到它!所以今天我会换个问题。你认为年轻人现在应该从事什么工作?在2023年,什么是令人兴奋、新颖和重要的事情?

K.K.: My generic career advice for young people is that if at all possible, you should aim to work on something that no one has a word for. Spend your energies where we don’t have a name for what you are doing, where it takes a while to explain to your mother what it is you do. When you are ahead of language, that means you are in a spot where it is more likely you are working on things that only you can do. It also means you won’t have much competition.

Possible occupations that are ahead of our language would be person-that-sits-with-you-when-you-are-ill, story-teller-for-the-company, AI-whisper, media-fact-check-verifier, wireless-troubleshooter, eugenic-adviser-diviner, roaming-robot-repair-person, influence-matchmaker, polyandry-therapist, applied-historian-in-residence, and maybe, full-time-note-taker.

My second bit of counsel is anti-career advice (taken from my new book Excellent Advice) and it goes like this:

Your 20s are the perfect time to do a few things that are unusual, weird, bold, risky, unexplainable, crazy, unprofitable, and looks nothing like “success.” The less this time looks like success, the better it will be as a foundation. For the rest of your life these orthogonal experiences will serve as your muse and touchstone, upon which you can build an uncommon life.

K.K.:我对年轻人的通用职业建议是:如果有可能的话,你应该努力从事一些没有专业术语的工作。把精力放在我们没有专业术语的地方,花时间向你的母亲解释你所做的事情。当你在语言之前时,这意味着你处于一个更有可能做出只有你能做的事情的位置。这也意味着你没有太多的竞争对手。

可能超越我们语言的职业包括陪伴病患者的人、公司故事讲述者、AI神秘人、媒体事实核查验证人员、无线故障排除专家、优生顾问预言家、流动机器人维修人员、影响力牵线搭桥人、一夫多妻治疗师、驻场应用历史学家,以及全职记录员。

我第二个建议是反职业建议(取自我的新书《优秀的建议》),是这样的:

你的二十多岁是做一些不寻常、奇怪、大胆、冒险、无法解释、疯狂、不赚钱、看起来与“成功”毫不相似的事情的完美时机。这个时期看起来与成功越不相似,它作为基础将越好。你一生中的这些正交经历将成为你的灵感和准则,你可以在其上建立一个不同寻常的生活。

以上是全文内容,感谢阅读

顺带一提:我太喜欢最后一段了。